No, you are not working for free until the end of the year | UK Recruitment News

Today is UK Equal Pay Day. While the campaign makes crucial breakthroughs for improving our working conditions, is the message losing its context?

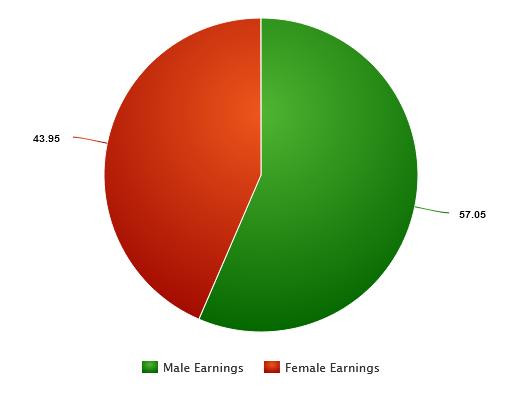

The meaning of the campaign is a simple one. Women in the UK take home less of the entire payroll budget than men. Calculated as a percentage, the UK gender pay gap in 2019 is 13.1 per cent.

So the campaign set a simple proposal: if annual earnings are normalised to what men take home, then women are essentially working 13.1 per cent of every year for nothing. In 2019, that comes out to 47 days of unpaid labour.

Because the data is always changing, the day is never fixed. Nor is it the same from one country to the next. Earnings in Britain are shared more equally than in the rest of the EU – 13.1% compared to 16%. The date therefore falls ten days later in Britain than for the rest of Europe.

Are you really working for free from now until new year?

But why the disparity? Since 1970, it has been a crime to pay men and women different wages for completing comparable duties. The law exists as part of the Equal Pay Act 1970.

So, does this mean that those organisations with a wage gap are risking prosecution? Or is it simply a case that nobody launches a lawsuit, so those old companies simply ‘carry on’ with their old ways?

Neither is the case. In reality there are very few cases of pay inequality for similar duties and jobs.

Gender Pay Gap reporting looks at the total cost of payroll, and its share across the genders. It means that the data is impacted by such basic (but ultimately significant) considerations as the gender make-up of an organisation, and representation within an industry.

These factors mean that it is unrealistic to say that the average female professional has stopped earning from now until the new year.

It’s not the bias that you thought it was – but it’s still not equal pay

However, this does not mean that – individually – women have the same chances to earn high wages as men. Last month, the ONS found that women earn a quarter of a million pounds less than men, over their entire lifetimes.

One of the reasons for the surge in interest has been the high profile cases around gender inequality in the media. Since publishing its pay data, the BBC has been hit by several claims of unfair pay by its female staff.

Again, the BBC has not broken the Equal Pay Act. But this time, it is the nature of its terms of employment which have sparked outrage. As on-screen talent commonly work as contractors, some individuals have been able to extract higher fees than their colleagues. These may include ‘consultancy fees’ or other extras. And, while the practice does not break the law, it produces unequal results in earnings. In this respect, the Equal Pay Day campaign has been valuable to talent looking to re-negotiate their own contracts at a higher rate.

Closing the gap

So how do we separate the case-by-case disputes from the bigger picture of wage inequality? From representation and reporting to salary caps on high earners, we look

Increase representation

One of the most efficient methods of addressing the gender pay gap is to increase representation. Essentially, this means aiming for a 50/50 gender split in the workforce for every profession.

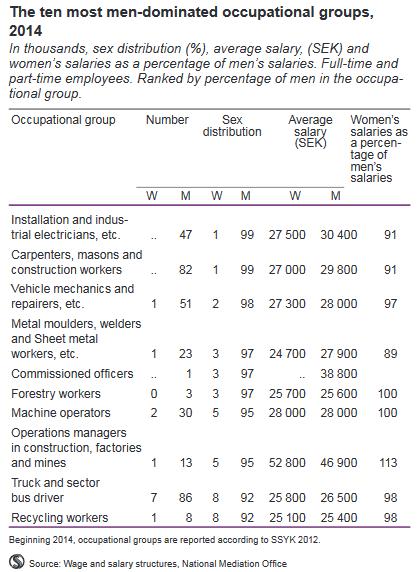

The lack of representation within some organisations and industries is one of the most misleading factors within the gender pay gap discussion. It means that, even in places like progressive Sweden the topic is hard to unravel.

The ten most male-dominated sectors in Sweden are largely construction or labouring roles. These professions have less than ten per cent female representation in their workforce. The resulting data found a 73% gender pay gap in these occupations. This is because the figures are calculated as share of total payroll. Yet in terms of actual earnings of individuals, the real pay gap was less than 10% in most cases. In one third of cases, women were actually earning the same or more than their male counterparts.

For gender pay data to truly represent the take-home pay of the individual, a 50/50 split in the workforce across every industry would be needed.

Link all salaries within your organisation and improve mobility

the second method would be to close the gap between highest and lowest earners within every organisation. As men tend to still occupy managerial positions, it is often the C-suite which accounts for the greater portion of the gender pay gap.

The most egregious example of this is perhaps in our educational system. While the teaching profession remains dominated by female professionals, it nevertheless has a gender pay gap which favours men. This is because department heads and principals are most often men. A reduction in the earnings gap between executive and entry level positions would address this workplace inequality.

How can this be implemented? One effective solution, proposed by economists and social scientists, would be to have all salaries as a fixed percentage tied to the company’s top earner. For instance, a receptionist might earn ten per cent of the CEO’s salary. That way, when the boss wants to treat him- (or her-)self to a pay rise, they have to increase the salaries of everyone else in the company, too.

Expand the scope of reporting

Finally, greater reporting will help to resolve undetected imbalances, but only over time. Mandatory gender pay gap reporting is only a couple of years old in the UK. And it doesn’t yet affect all employers.

By increasing the scope of compulsory public reporting, we will have the data needed to make real changes. But we will also need to arm ourselves with the correct information and understand what stories the numbers are telling us – and which are being misused to create a different narrative.